Improved classroom ventilation could reduce COVID-19 risk

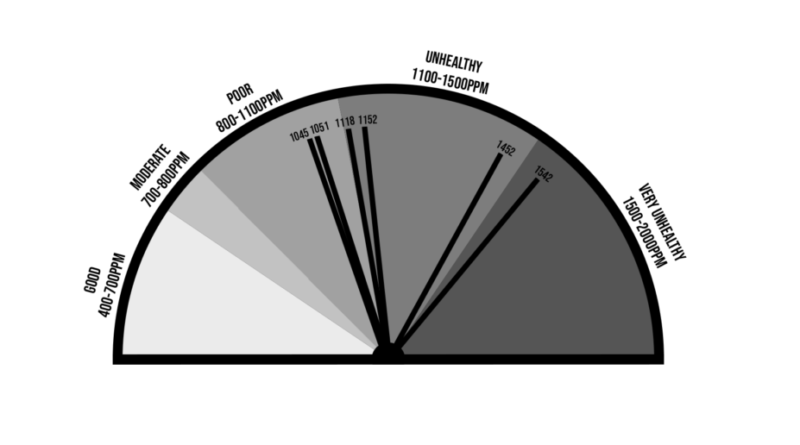

GRAPHIC: Four of the six classrooms monitored for CO2 by the HUB had maximum CO2 levels between 1,000ppm and 1,200ppm, while two exceeded 1,450ppm. (Data collected by Max Davis-Housefield, CO2 safety guidelines from greenecon.net)

By Max Davis-Housefield,

BlueDevilHUB.com Staff–

Because COVID-19 is an airborne virus, good ventilation is one of the best ways to prevent infection. The CO2 levels in a room can act as a proxy, or stand in measure, for the amount of COVID-19 that could be present in that room if someone inside is infectious.

In an investigation, the HUB sought to analyze the effectiveness of the ventilation systems in several DHS classrooms by measuring the buildup of CO2. The investigation found that, while variable, the levels of CO2 in the classrooms were not dangerous on their own. However, they did indicate the potential for increased COVID-19 transmission.

“Traditionally, classrooms have always been underventilated,” said Dr. Dustin Poppendieck, an environmental engineer with the National Institute of Standards and Technology. This is because “it costs money to treat air … to humidify it, or heat it, or cool it.”

CO2 monitoring is one of the best ways to find under ventilated classrooms and mitigate the risk of students contracting COVID-19.

“(It) is not a direct measure of risk,” Poppendieck said, but “it’s a proxy of what we emit as humans.”

In a poorly ventilated room, these emissions can build up. Poppendieck compared it to old movies of people smoking in a bar with the smoke expanding all around them. “COVID-19 can build up like that too,” Poppendeick said.

Portable high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters can help to remove COVID-19 from the air, something that is not reflected when using CO2 data as a proxy for COVID-19 buildup because the CO2 particles themselves are too small to be removed. However, for this process to work, the filters have to be functioning properly.

“They have to be running, they have to be adequately sized for the space, and they have to be on the design(ed) settings. Typically they tend to get turned down or off (because of their loud noise),” Poppendieck said.

Oftentimes the filters are improperly sized and “aren’t moving enough air through them,” Poppendieck said.

According to Poppendieck, buildings are built for “a designed number of students … (with a specific) age and activity level.” The ventilation systems are supposed to supply between 6.4 and 7.3 liters of fresh air into the room per person per second.

However, these standards were set before the pandemic and were primarily designed to prevent the circulation of odors.

“Many people have said that we should double that to have effective ventilation, so we should be at 10 to 14 liters per person per second,” Poppendieck said.

The age of the ventilation systems does not have a significant effect on the indoor air quality. While the standards for indoor air quality have changed throughout the decades, decreasing in the 1970s before going back up, the problems indicated by high levels of CO2 typically lie in malfunctioning or misused equipment.

To test the effectiveness of ventilation systems at Davis High, the HUB measured the CO2 levels in six different classrooms in November.

CO2 is measured in parts per million (ppm), with the typical level outdoors is around 400 ppm. While levels below 1,000 ppm are considered safe, anything over 1,000 ppm can lead to negative effects for students.

According to Poppendiek, at high levels of CO2, such as around 10,000 ppm, “you’ll have drowsiness, and reduced mental impact and cognitive functioning.”

“It’s actually kind of controversial,” Poppendieck said. “Some studies have shown airline pilots’ cognitive abilities decreasing above 1,000 ppm. There’s other studies that show students having no ill effect (at) about 2,000 ppm.

“It’s likely there are issues that get worse as you get higher, somewhere between the 1,000 ppm and 4,000 ppm level, but it’s unclear where it happens and to what extent it happens,” Poppendieck said.

The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) recommends that the CO2 concentration should not be more than 700 ppm above outdoor air. This translates to around 1,100 ppm using 400 ppm as the outdoor standard.

The highest level of CO2 the HUB recorded was 1,542 ppm in Sydney Lundy’s room, S-08. The S-wing was constructed in 1972, after the standards had been revised downwards — something that could explain the disparity.

The N-wing portable buildings also showed concerning readings with a high of 1,452 ppm measured in N-08. Other newly constructed classrooms seemed to have average CO2 levels of around 1,000 ppm.

Mike Kanna’s room, L-27, reached a peak of 1,152 ppm. He noticed that his “room numbers go predictably up and down during (his) third period prep and (during) lunch.

“My numbers might be ameliorated by my windows being a crack open,” Kanna said. “Does make the room cold, though.”

Lundy agrees that it can sometimes be difficult. “I keep the doors open when weather and exterior noise permits.”

Denise Brogan, the Director of Maintenance & Operations at Davis Joint Unified School District says that the heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems at Davis High, which were installed in 2019, conform to state standards.

With the onset of COVID-19, DJUSD ensured that all ventilation systems were fitted with a MERV-13 filter, one of the most effective filtration systems.

The district was well ahead of UC Davis, which still hasn’t completely updated all their buildings.

None of the units at the high school needed updating in order to be fit with the MERV-13. Brogan added that every HVAC unit “has an adjustable damper that allows outside air into the room.”

However, she did not confirm that these units were always set to bring in 100% exterior air, something that is strongly recommended by ASHRAE and greatly increases the effectiveness of the ventilation system.

Poppendieck is not really concerned by the levels of CO2 in the rooms monitored by the HUB. “Bad is really bad, (but) everything else … may be good and may not.”

He believes that poor ventilation is really an equity issue. “A lot of our poorly performing schools from an air quality perspective are in our lower income neighborhoods, and are in the places where we just aren’t investing a lot of money,” Poppendieck said.

According to Poppendieck, the best thing DHS teachers can do to improve the air quality and circulation and bring down the risk of COVID-19 infection is to open all doors and windows. They should also ensure that their portable air filters are turned on to the maximum settings despite the noise.

“People have always been saying ‘let’s cut the energy budget (by recirculating the air). In some ways, we’re saving the planet by reducing our energy load.’ But we (may be) harming the occupants inside of those rooms,” Poppendieck said.

Statistically, students in classrooms with CO2 levels of around 1500 ppm could be breathing in 50% more COVID-19 particles than students in classrooms that average about 1000 ppm if a positive case is present.